In 2016, I gathered in Kreuzlingen with some 120 relatives from Britain, South Africa, Germany, Switzerland, the United States and Canada. We were there to hear about the history of the Swiss Binswangers, a family that for four generations operated the Bellevue Sanatorium, which treated members of royal and wealthy families from around the world.

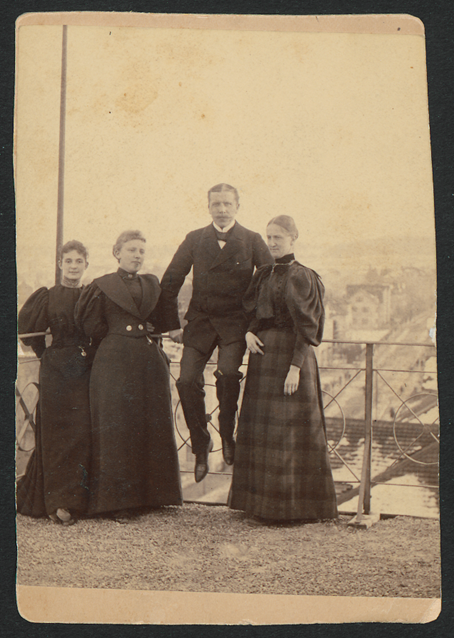

Next week I will visit Augsburg, where we will travel further down our larger family tree to meet the descendants of Moses Binswanger, my great, great, great, great grandfather. Here he is:

In taking a look at the Moses family, I will draw heavily from a short history of the Swiss Binswangers by Richard Binswanger. I will also draw from extensive research put together by family historians Andreas Binswanger and Walter Ertz and family genealogist Jane Schinzinger.

Moses Binswanger, a Jewish peddler, who was born in 1783 in Huerben, not far from Munich. His grandparents lived in Binswangen, 33 miles away, and they mostly likely took the name of that village as their last name when they moved first to Osterberg and then Huerben. Jews had lived in Huerben since 1518 when they had been driven out of Donauwoerth, where they had controlled much of the trade in salt.

In 1670, Count Maximilian of Liechtenstein asked the Emperor for permission to expels the Jews from Huerben but the request was denied, and five years later the count allowed the construction of a synagogue and a house for the rabbi. Ritual slaughter of animals was allowed, and for each cow or large animal slaughtered, the animal’s tongue had to be delivered to the manor–although in 1717, a new rule allowed a fee of 15 Kreutzer to be substituted for the tongue. For small animals, a fee of five Kreutzer was charged.

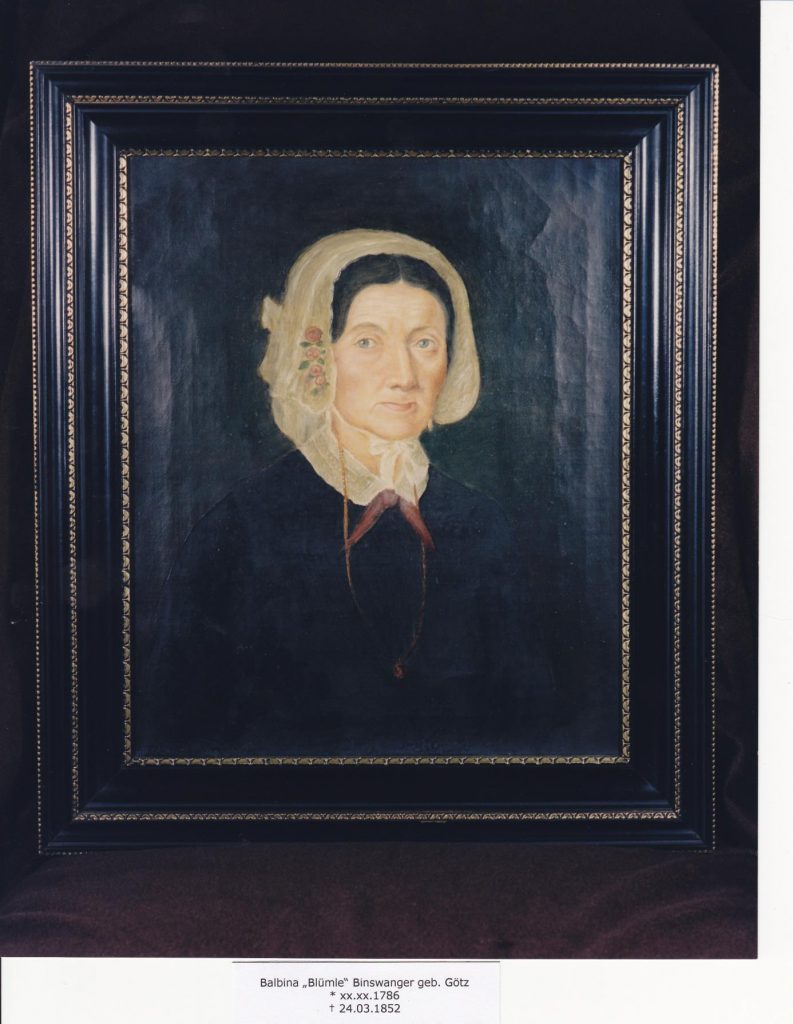

Moses married Bluemle Goetz, who was from the village of Fischach, about 14 miles away where Jews had lived since about 1570. The Jews of Fisbach were moneylenders, and also traded horses and cattle. Even today, farmers in the region tell stories of how the Jews had long been considered so honest in business dealings.

During the 30-years-war, which lasted until 1648, the Jews fled to Augsburg. Although they were allowed to return to Fisbach after the war, they were told they could only live in five houses. They moved in, and expanded each house until, by 1743, there were 113 people living in those five houses. Neighbors complain constantly and finally, in 1802, they were allowed to build more housing. A Jewish synagogue was built in Augsburg in 1739, and a cemetery in 1774. Today, one memorial carries the inscription: “Dedicated to the victims of the racial persecution 1933-1945. In Memory of the Dead: An Admonishment for the Living.”

The earliest city records of Binswangers in the region go back to 1799, when Salomon Binswanger, apparently facing difficult times, sells his pews–men’s seat No. 4 and women’s seat No. 20 in the upper Synagogue to Simon Laundauer, a protected Jew of Huerben for 35 florin. A month later, three Jews, including Seligman Binswanger, seem to be doing better because they contract with three master carpenters to build three new houses, paying 600 florins in upfront cash. (In 1818, Seligman Binswanger, now a widower in Huerben, transfers his house No. 123 to his son Marx. The house has a living room, an adjoining bedroom, a kitchen, a bedroom under the roof, wood storage and furnishings.) Seligman is also the father of Moses Binswanger.

The first records of Moses Binswanger date to 1809 when he makes a request of the Royal Bavarian Administration to be granted residency in Osterberg. The document references an attached statement noting his intention to marry Bluemle Goetz from Fischach. Including a dowry from his father of 100 florins, a dowry from Bluemle’s family of 625 florins, Moses’s personal savings of 300 florins, the couple ill start life flush with 1025 Florins. Moses is pronounced “financially responsible,” and is granted his request to be excused from military service. Moses is 26 years old at the time. As a subject of the Osterberg manor, he was assigned a lot for the construction of a residence.

The marriage contract of Moses and Bluemle Goetz is registered in the Manor Osterberg files in 1811. This time, Moses’ name is given as Moises Loew-Binswanger. The contract includes a prenuptual agreement of sorts. If the husband dies in the first year of marriage without a child having born, the wife will receive everything she has brought to the marriage. If he dies in the second year, she only receives half of her contribution to the marriage, but retains the right to occupy the couple’s residence. If the wife dies in the first year, the husband will return everything received her to her relatives. By the third year, the husband becomes the sole heir of the money. Many of the documents are written in Hebrew and written alternatively as Moses, Moises or Moyses.

The is Bluemle Goetz:

After Moses and Blumle married, they moved to Osterberg where Moses worked as a peddler selling textiles and glass door-to-door. He traveled to villages as much as 45 miles away, most likely on foot.

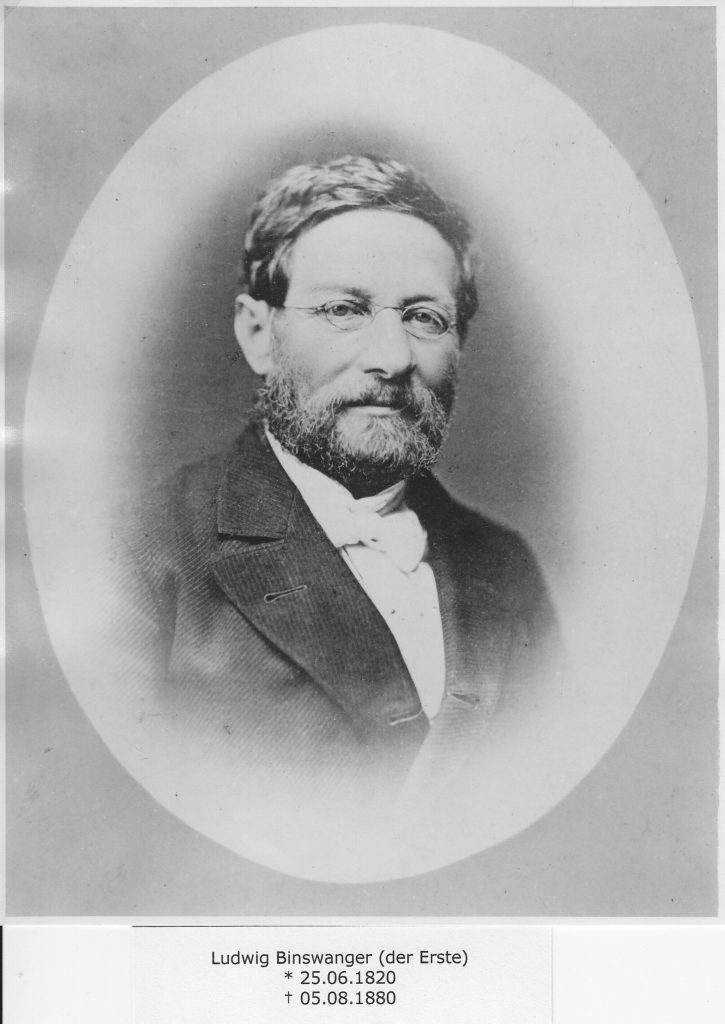

Moses had nine sons of whom four went to the United States. One of those sons founded Binswanger Glass, which would develop into one of the country’s largest window makers. Another son would stay in Germany and develop a large vinegar and beer brewing company. Yet a third son, Ludwig born in 1820, was trained in Germany as a doctor and moved to Kreutzlingen to take a job in a psychiatric hospital.

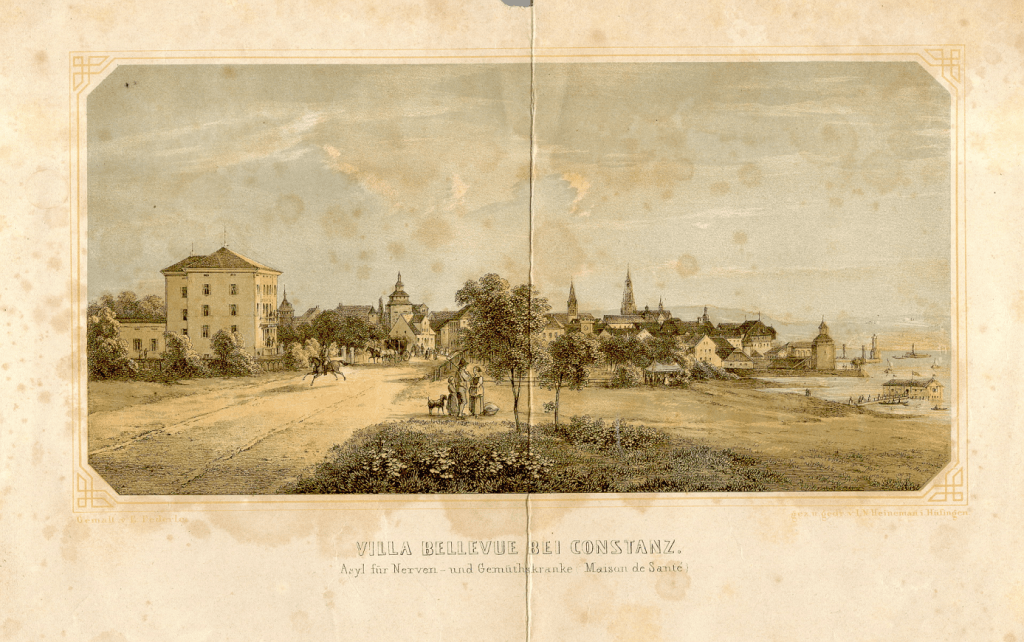

Seven years later, Ludwig married Jeannette Landauer, a very wealthy woman, and with her money opened a private psychiatric clinic, the Bellevue Asylum, in Kreutzlingen, Switzerland, right on Lake Constance on the border with Germany.

As Richard Binswanger writes in his short history of the family: The asylum was founded in what was originally a convent and later became the publishing house “Belle-Vue”, which had become very well known for publishing liberal literature and promoting progressive ideas, written by German political refugees. The publishing house was not regarded favorably in Germany, and with the conservative backlash in Europe after [the revolution of]1848, the publishing house lost its economic foundation and was sold to the Binswangers.

When the Sanatorium opened, it ran the following advertisement showing the view that Belle-Vue had of Lake Constance.

Ludwig and Jeannette’s idea was to allow patients to move freely on a campus shared with the staff and the doctors. Once a week the patients dined with Ludwig’s family. This approach came out of the reform movement in psychiatry in the mid-19th century, which believed that the patient’s needs should always come first. That approach was followed at Bellevue right until the sanatorium closed in 1980.

Villa Belle-Vue. The building once house a progressive publishing house.

Villa Belle-Vue. The building once house a progressive publishing house.

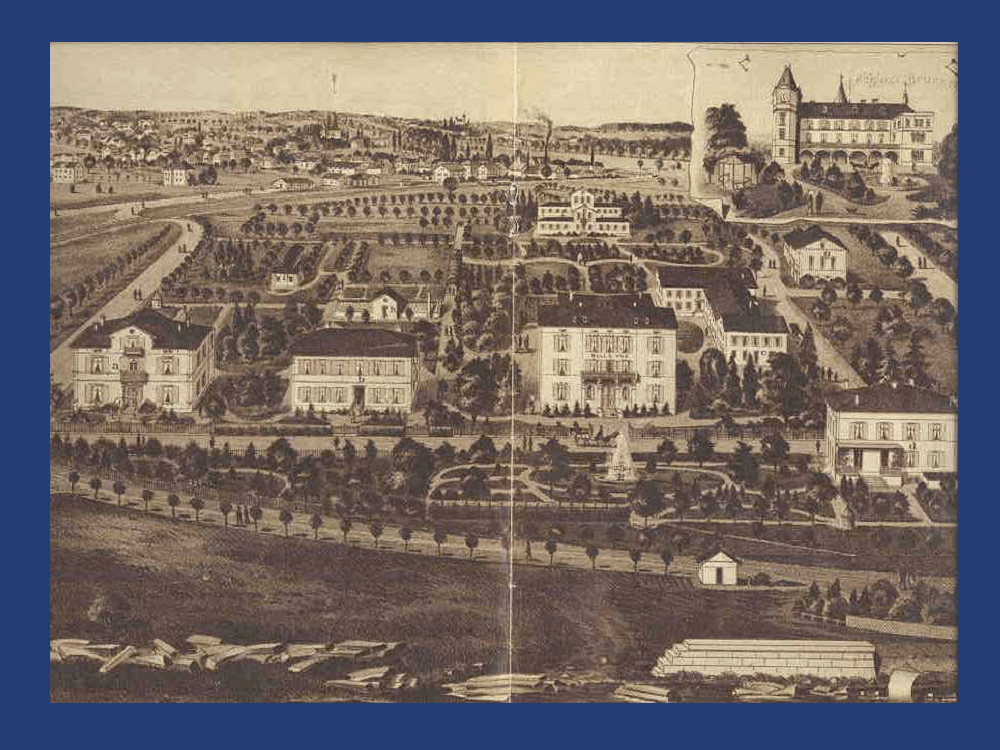

The Sanatorium was successful, and gradually added elegant homes to house the wealthy patients.

Ludwig had never been a very religious Jew. In 1848 he did make “a blazing speech for the emancipation of the Jews in Munich.” Liberal activists involved in the 1848 revolution experienced a crackdown by monarchists, and, by some accounts, Ludwig moved to Switzerland to escape the crackdown.

Although Ludwig had observed kashrut in Munich, when he moved to Konstanz, a German city on the border with Switzerland, that became difficult. Konstanz had expelled Jews from the city 400 years before and there was little or no Jewish community. Since Ludwig wanted to participate in political life and in the community, he converted to Christianity and joined the church at Kreuzlingen, a Swiss town nearby. His Jewish family was unhappy with that decision and there are reports that when his mother was on her deathbed, members of Ludwig’s family were not permitted to see her. When Ludwig’s siblings created the Moses and Blumle Binswanger Foundation in the 1900s to provide scholarships for members of the family, Ludwig was not a part of that effort.

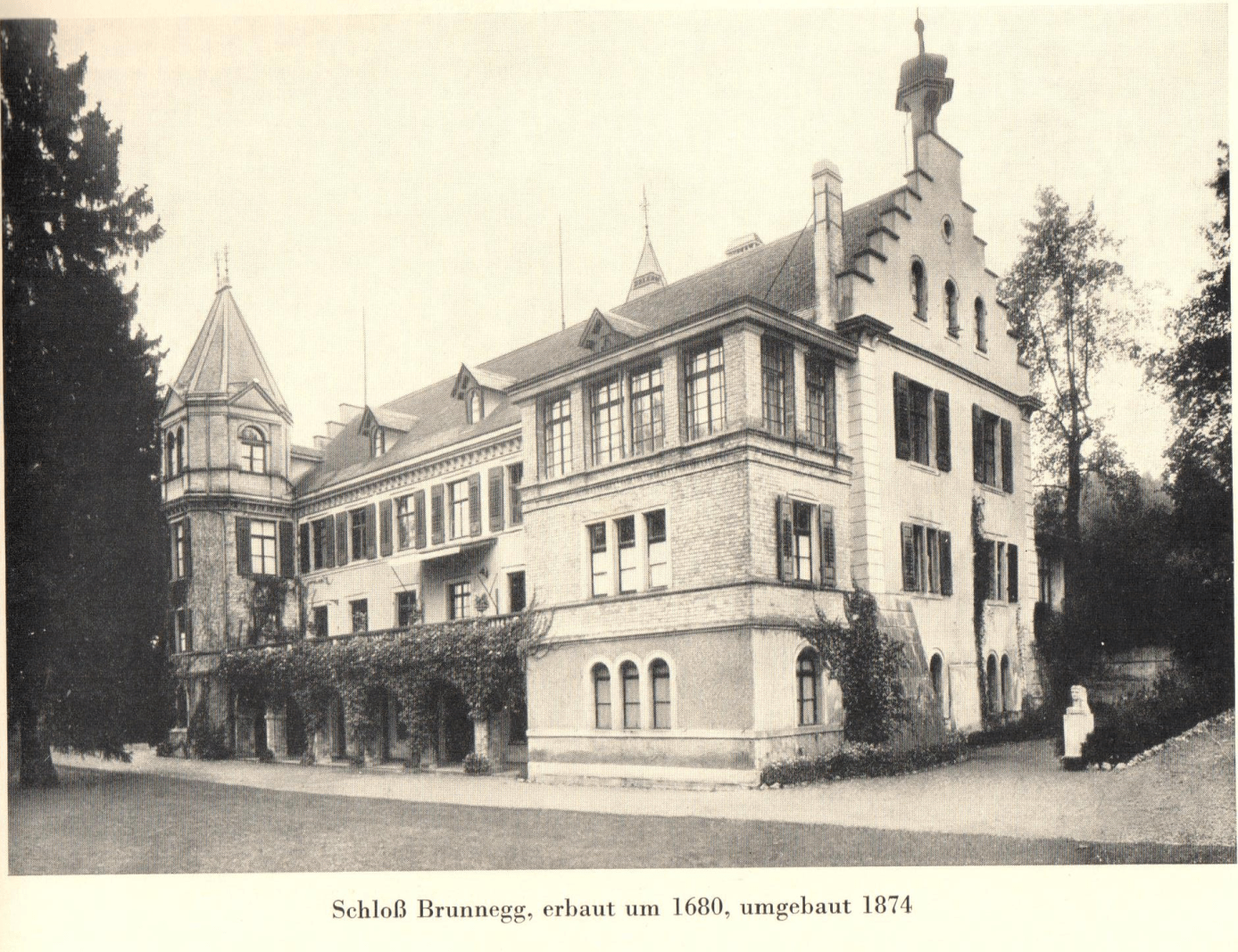

Ludwig and Jeanette’s Sanatorium was successful, and the couple bought a rural estate, Brunneg Castle in 1874. That castle, which was originally built in 1680, became the family’s home for more than a century. It is now the Schloss Brunnegg Hotel. Andreas and Christophe Binswanger recall how there were two living rooms in the castle. In the summer, all the living room furniture would be moved to the living room on the north side of the house, which was cooler. In the “winter house” the living room was in the south and all the furniture had to be moved to that living room. Christophe Binswanger, later a World Bank economist, remembers the attic being full of cushions and large suitcases with drawers where the kids enjoyed playing. It would be the home first of Ludwig 1 then Ludwig II, then Robert I (my great, great grandfather) and then Otto ll. Since the Binswanger philosophy was that patient needs always came first, there were few boundaries between the patients and the family. Patients often ate with the family and the kids often spent time in the Asylum. Some of the kids were fine with it and loved running around the asylum. One Binswanger, however, was less enamored of the experience and wrote a book based on his memories growing up on the Sanatorium.

Ludwig I and his son Robert I bought the surrounding land, establishing a modern farm that provided the market in Constance with dairy products among other farm products. The family had 100 cows, and family members recall drinking milk directly from the teets of the cows. Later, when there was a tuberculosis epidemic among deer that was infecting cows in the Swiss Alps, Otto became concerned and sold all his cows. Visiting the farm in 2016, I thought it looked more like an elegant estate than a farm with its handsome barns and stables. The hay was stored in the barn below. There were also silos to store the grass. It was mixed with salt to feed cows in winter. The pigsty was built of brick. When the government planned to build a tunnel under the farm for a highway, the family objected on the grounds that the noise would disturb the pigs.

The Brunnegg Farm

The Brunnegg Farm

Robert Binswanger, my great great-grandfather, took over as head of the sanatorium in 1880. He married Bertha Hasenclever, who came from a wealthy Dutch family and whose riches help to finance an even more rapid expansion at Bellevue.

Robert Binswanger’s wife Bertha Hasenclever, wealthy Dutch woman, provided the wealth for much of Bellevue’s expansion.

Robert Binswanger’s wife Bertha Hasenclever, wealthy Dutch woman, provided the wealth for much of Bellevue’s expansion.

Robert and Bertha had five children including Ludwig 1881-1966, who would become the next head of Bellevue and a famous psychiatrist, Otto ll 1882-1968, Robert II, 1892-1963 and my great-grandmother Anna, 1877-1941.

Writes Richard Binswanger:

During Robert’s lifetime, Bellevue expanded and flourished. He created a magnificent park of around ten hectares with 15 houses for only 60 patients, where they lived, sometimes only one individual in a house together his staff. In one of these villas. I spent the first happy twelve years of my life. This “Bauwut” – building obsession – of Robert was one of the causes of the later decline of Bellevue, as the preservation and upkeep of the architectural substance far exceeded the financial capacities of the sanatorium. But until that point, almost sixty years would pass. Under the leadership of Robert I, Bellevue had the greatest economic success in its whole history.

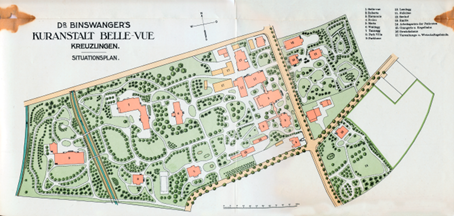

Map of the Belle-Vue campus under Robert Binswanger

Map of the Belle-Vue campus under Robert Binswanger

The Bellevue Kitchen Staff was enormous.

The Bellevue Kitchen Staff was enormous.

There was a large dining hall for both the 60 patients and another 40 or so staff.

There was a large dining hall for both the 60 patients and another 40 or so staff.

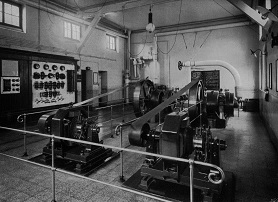

There was an engine building that housed what looks like two generators to power the electricity on the campus.

The Generator Room

The Generator Room

The asylum was now a massive facility. The administration and kitchen facilities alone required a large building.

A view of the dining hall from the outside.

A view of the dining hall from the outside.

A large, high-ceilinged central kitchen produced food that was prepared in iron cookware that was then taken by car to each patient’s house. Richard remembers his father would alternate his fare between food cooked for the employees and that prepared for the patients so that he knew what everyone was eating. Once a week his parents had meals with the patients. That included the countess of Bern, a Miss Kernix who was bipolar.

There was a butchery in an annex of the kitchen. “We all loved the kitchen,” Richard recalls. The parents would complain, but the cooks would always give us something to eat. There was a Mr. Raas? who trained the cooks. He had an unlimited supply of ice at a time when that was rare.

More modest was the “Middle Building” where the Physical therapist and housekeeper lived. The ironing was also done here and there was a big stove on which the flat irons were heated.

Middle Building

Middle Building

While most patients were given a lot of freedom, there was also Parkhaus, a special facility for patients with more severe problems.

Parkhaus was a special facility for patients requiring more acute care.

Parkhaus was a special facility for patients requiring more acute care.

Many patients were housed in elegant homes.

Villa Felicitas

Villa Felicitas

Park Villa

Park Villa

Villa Landegg

Villa Landegg

Villa Waldegg

Villa Waldegg

Villa Marika

Villa Marika

Villa Emilia

Villa Emilia

Villa Roberta

Villa Roberta

Villa Harmonie

Villa Harmonie

In addition to the houses pictured above there was the villas Bodan, Tannegg, Seehof and the Orangerie. The Orangerie had a bowling alley. There was also a building for the gardeners.

The villas were built to house the many wealthy patients Bellevue catered to. Among the patients was Hellene Muller who came from one of the wealthiest families in the Netherlands. Her family owned Muller and Co. Helene, studied art under H.P. Bremmer and began collecting art. She was one of the first European women to put together a major art collection and among the first collectors to recognize the artistic genius of Vincent vanGogh. She ultimately collected 97 paintings and 185 drawings by van Gogh. She and her husband donated their entire collection to the state along with their 75-acre forested estate, which is the site of the Kroller-Muller Art Museum.

Robert’s brother, Otto, also made his mark. He married Henriette Baedeker 1859-1941. According to Richard’s history, Otto “was professor at the medical faculty of the University of Jena GE and Chief of its Psychiatric University Clinic for several decades, which under his leadership became one of the most famous in Europe.

He treated many famous figures of his time, among others Friedrich Nietzsche. He was one of the first psychiatrists of his era to recognize the importance of Sigmund Freud and was considered a scientist and clinician of the same significance as Alois Alzheimer. He was the first to describe hypertensive vascular encephalopathy, a form of dementia, named “Binswanger’s disease” by Alzheimer himself. His children were Reinhard 1884-1939, Margaretha 1885-1931, Amelie 1887-1977, and Lilly, known as Hertha 1892-1966.

The sanatorium’s solarium that was a popular gathering place.

The Solarium

The Solarium

The solarium was a glass hallway that extended out from the main building and wrapped around the entry to the sanatorium. The sunlit glass hall, glassgung as it was called, was art nouveau, perhaps designed by the architect Heinrich Jurgensen, a German architect who spent much of his career in Denmark. It was often used for entertaining.

The glassgung was used for the filming of Martha, a critically acclaimed drama by Reiner Werner Fassbinder made for German television that came out in 1973.

Robert’s second wife was Marie-Louise Meyer, called Mietzie, 1871-1941. The couple had two sons: Paul Eduard, called Edu, 1898-1959 and Herbert, called Hebi, 1900-1975.

Marie-Louise was a beautiful and charming woman, and when her husband died, she left their home at Schloss Brunnegg and moved into her house in Uttwil on the Swiss side of the Lake of Constance. There she gathered many artists and writers.

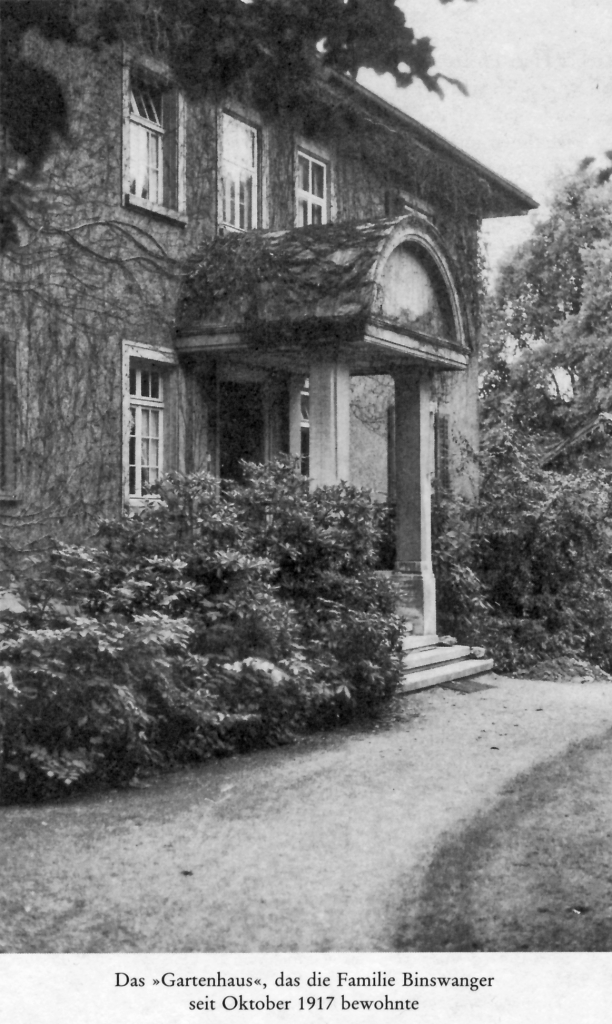

Ludwig Binswanger ll followed his father Robert as chief medical director of Bellevue in 1911. He lived on the Bellevue campus in the Gartenhaus pictured below.

In retrospect, those were good years. Bellevue became one of the most famous private psychiatric clinics in the world, receiving patients from all continents. Patients included princes, the mother of Queen Elizabeth II and captains of industry. Many famous artists also spent time at Bellevue, including the painter, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, the dancer, Vaslav Nijnsky, the actor Gustav Gründgens and the art historian Aby Warburg.

But those good times would not last. First there was World War I. During the war, the sanatorium faced economic difficulties because foreigners, who accounted for 90 percent of its patients, had to leave Bellevue amid the rise in nationalism. “We never recovered from the crisis,“ says Richard, the historian.

Even so, the Sanatorium remained a center of social and intellectual activity. Ludwig Binswanger studied under Jung. Jung had introduced Binswanger to Freud in 1907, and the two had become good friends. A collection of their correspondences was collected in a book some years ago that has been translated into English. When Freud became ill, he left Vienna to visit Binswanger. Freud also referred many of his patients to the Sanatorium.

The two remained friends even though they differed in many of their views. Binswanger, for example believed in existential therapy. Binswanger uses a German term “Dasein,” which means literally “being there.” Some translate it as human existence, or a sense of moving beyond oneself. Heidegger translated Dasein as an openness, as a meadow is an openness in a forest. Sartre calls it “nothingness.” There is also this concept that you can extend yourself into the world as with a telephone or telescope and the world can come into you, as in an artificial hip, or the society and cultural order into which we are born.

When we are enslaved by social norms there is a condition called “falleness.” Following Martin Buber, Binswanger adds the more positive notion of “we-ness” for love and an openness to each other. Binswanger sees this as “being-beyond-the-world.” Existentialists recognize that life is hard. You never have enough information to make a decision. And you will die. We can’t choose not to choose. We feel anxiety or dread toward the future. Anxiety is a condition of being human. We are not like a table, eternal. We are always about to slip off into nothingness. If we do not do what we know we should, we feel guilt. We feel regret over past decisions that hurt us. We feel regret when we choose the easy way out. When we lose our nerve, there is a focus on being authentic, which is to be aware of yourself and your circumstances, your social world, the inevitability of anxiety of guild and death. It means involvement, compassion and commitment. The ideal of mental health is not happiness. The goal is to do your best. If you trade possibility for actuality, you are inauthentic. You have given up. Each person is unique, so each person has a different way to be authentic. If you are too busy to notice the moral decisions you must make, you are living in what Sartre calls bad faith. The neurotic person is aware of the choices that have to be faced and is overwhelmed by them and so freeze or panics. Or they find something small, a phobic object or compulsion, a target of anger or a pretense of disease. Although you can address the symptoms of all this, an existential psychologist says you need to face the reality of Dasein. The existential psychologist tries to discover the client’s world view. Their everyday lived world. Your physical world, your social relations, your culture. What is it that is most central to your sense of who you are? Binswanger wants to know your view of your past, present and future. Are you forever trying to recapture golden days? Do you live in the future always hoping for a better life? Is life a complex adventure or here today and gone tomorrow. How do you treat space? Open or closed? Cozy or vast? Warm or cold? Is life a journey or is there an immovable center? The existential psychologist allows the patient to express the full richness of their lives in their own words and in their own time. If there are dreams, the EP wants to know what you think they mean? Therapy involves an encounter, an opening up. It’s a dialogue between psychologist and patient. The goal is the autonomy of the client. Like teachiing a child to ride a bicycle, you can only help people become more fully human if you are prepared to release them. This approach is considered unscientific by most psychologists today. Proponents say it offers a better, more refined way toward understanding human life.

There is a famous case of Ellen West who as a teenager would say “either Ceasar or nothing.” At 17 she writes a poem asking the Sea-King to kiss her to death. When a friend comments on her weight, she begins to obsess about being fat. When parents interfere with an engagement, she becomes despondent. She marries her cousin in hopes of changing the trajectory of her life. But over time she becomes anorexic and twice attempts suicide. She is finally sent to Kreuzlingen where she lives comfortably with her husband. She is put under the care of Ludwig Binswanger. She writes a poem about her condition:

I’d like to die just as the birdling does That splits his throat in highest jubilation; And not to live as the worm on earth lives on, Becoming old and ugly, dull and dumb! No, feel for once how forces in me kindle, And wildly be consumed in my own fire.

She had divided life into the ethereal, pure world of the soul, writes Dr. C. George Boeree, and the “tomb world” tied to a bourgeois, corrupt society and a body with its base needs. Her anorexia, which reduced her body to a skeleton moved in that direction. The case is famous because Ludwig Binswanger chose to listen to her and let her express her perspective.

Because she continued to attempt suicide, she was given a choice: She must be committed to a special ward for serious patients where she would probably continue to deteriorate, or she should be released, in which case there was a high likelihood she would commit suicide.

Back in the real world she does better. She eats chocolates and writes letters. But then she takes a lethal dose of poison.

Under the final medical director, Wolfgang Binswanger, the philosophy of the sanatorium moved more toward the self-actualization philosophy of Carl Rogers. Wolfgang even experimented with drugs according to his wife.

The sanatorium gradually fell into decline following the retirement of Ludwig ll. The family faced many sorrows that also weakened the institution.

Robert III, the son of Ludwig II committed suicide as did Beat, son of Eduard. There seems to have been a tendency toward depression. My great-grandmother, born Anna Binswanger, attempted suicide in 1929. But there were other tragedies as well including the death of Peter, son of Kurt in a military aircraft crash as well as the early death of Werne, who the family had hoped would restore and revitalize Bellevue after the Second World War. There were also severe economic crises after both World War I and II, followed by the decline in the wealth of the aristocracy and the broader economic decline that gradually wore away at Bellevue.

The farm survived for a while. Andreas Binswanger, the historian, took over the farm from his father in 1968 and introduced computer systems to optimize the production of grain, apples and other products. He figured out that the cows were losing money and persuaded his father to sell the cows. Richard, who lived in the main house with his father, Otto, remembers waking up to a big fire at the barn. When Andreas retired, there was nobody to take over the farm and so it was sold to become a school for adolescents with learning disabilities.

I was 12 when I visited the sanatorium with my family. We had dinner with Wolfgang Binswanger and his wife and children. We received a tour of the sanatorium and I remember the patients painting in what must have been the glassed-in halls of the solarium. The campus was pretty and park- like. It may have had as many patients as it did earlier in the century, but they were probably less wealthy and that must have made it harder to charge high fees. The aristocracy that wase so important to Bellevue’s prosperity, was much in decline after World War I and all but gone by the end of World War II. The property was sold to a developer in 1980.

I look forward to learning more about this amazing family next week when I leave for Europe.